Narrative Layers

Welcome back to my series attempting to answer the question: What is House of Leaves? If you missed it, here’s Part 1: The Navidson Record, where I introduced the centermost narrative in the book. Today I’ll be ascending to the next narrative layer, that of The Navidson Record’s imaginator and critic: Zampanò. There will be spoilers, though again I’ll do my best not to ruin the experience for any prospective readers.

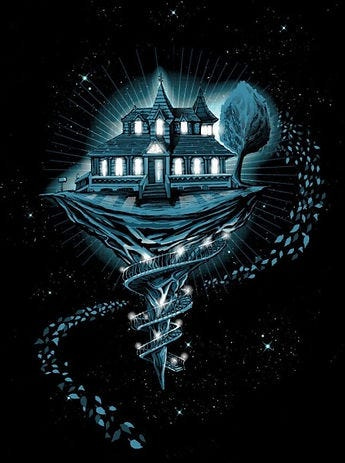

(For another narrative layer, the album above is by author Mark Z. Danielewski’s sister Poe, and itself references House of Leaves.)

To recap: The Navidson Record is a film created by Will Navidson, apparently out of real footage of himself, his family and his new House on Ash Tree Lane. Its release followed two previous, incomplete recordings of explorations into the House; reactions to which are included in the film, thanks to interviews conducted by Will’s partner Karen Green.

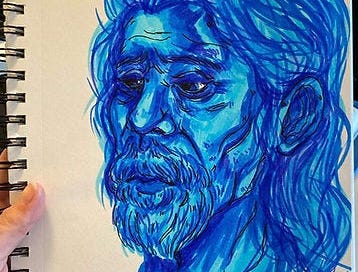

Zampanò

So to pick back up, Zampanò conjured The Navidson Record and dozens of articles about it out of thin air in his creation of the manuscript that would eventually become House of Leaves. If you haven’t read the novel, you probably have a couple quite reasonable questions: who is Zampanò? What articles?

Does it help if I say that I’m asking the exact same questions, even after two complete journeys through this text?

Taken at face value, Zampanó’s manuscript is a thoroughly researched analysis of The Navidson Record, including details before, during and after the film’s production and in discussion with many articles written about the film in the years since its release. It’s a longer form of the critical analysis essays I wrote in the upper years of my bachelor’s degree; a much longer and more thorough version of what I write in these posts twice a week.

Zampanò was a man in his 80s, who by all accounts had been blind for most of his life. In moments of confusion he would speak different womens’ names, speculated to be past romantic interests. He enjoyed walking in his apartment’s small courtyard, accompanied by dozens of stray cats. It remains entirely unclear how the idea for The Navidson Record and its critique struck him, but it seems unlikely that he inherited it from anyone else (like Johnny later does from Zampanò); his chaotically scrawled manuscript is entirely his own.

I ended the previous post by referring to Navidson’s fixation on the House’s ominous interior as an obsession. We can certainly see a reflection of this in Zampanò’s manic creation and how he shuts out the world. But uniquely among the three (four?) narrators, we don’t see the genesis of Zampanò’s obsession beyond a vague implication of it stemming from his age, blindness and potentially the people and relationships he has lost.

To me this represents the real dangers of an empty life; the way the mind can begin honing in on random ideas that feel revelatory until you take a step away to find perspective. But I tend to believe Zampanò’s manuscript began as a genuine creative endeavour, and only later did he find himself drawn to the same alien darkness that consumes Navidson.

At that point, Zampanò seems to have responded in exactly the same as his protagonist: arming himself with scientific and literary reason and analysis to try to make sense of the void. Some of the strangest sections of Zampanò’s manuscript involve detailed scientific analysis of the House, both in- and outside the fiction of The Navidson Record: an entire chapter explores the scientific and literary significance of echoes, while another goes into detail on attempts to carbon-date samples collected from the House (the deepest of which seem to predate the formation of our solar system — did I mention I love this book?).

An Academic

He qualifies his analysis through references to works and insights of other writers, proper for such an academic project and as I discussed back in my footnotes post. But like any manic, sleep-deprived undergraduate writing against a ticking clock, Zampanò plays fast and loose with his sources. Many are completely fabricated, others have real authors, others exist but Zampanò’s quotes from them are fake.

There is a monstrous number of them, but the internet is full of heroes of all shapes and sizes: four years ago, a redditor shared a list of their research into the veracity of each and every one of Zampanò’s references. What’s particularly impressive to me is that Danielewski (and Zampanò) manage to weave all of these in so naturally.

Every article feels perfectly tangential to the subject at hand, exactly as if you were writing on a new and unique topic but consulting authors in areas that you’re bordering against. Just look through the titles and you’ll see a vast swathe of the human experience; the breadth of subjects covered is why House of Leaves has been called an ‘encyclopedic novel’.

But Zampanò’s scholarly bent also come across as powerful satire at times. He maintains a strict, academic air while devolving into long, painstaking tangents and while documenting and negotiating disagreements between his invented sources, often over the meaning behind a single frame of the film. But those details remain in the shadow of the simple satirical fact that Zampanò is a blind man writing feverishly about the meaning of a visual medium — which doesn’t exist.

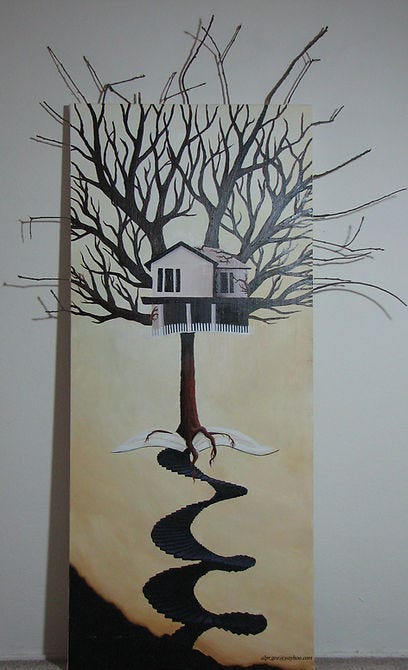

Ergodic

This book has also been called ‘ergodic’, meaning difficult to traverse. It’s not a matter of vocabulary or font size either: it takes physical and mental work to read this book.

House of Leaves may be 736 pages long, but only 528 make up its actual chapters. There is a plethora of appendices and exhibits in the back of the book that you can read and examine whenever you want; the text points you to a few of them at times, but each reader must decide for themselves when and whether to engage with those materials.

If you’re new to books with fictional footnotes, you must decide whether to pause mid-paragraph or even mid-sentence to see what additional context is being added, or whether to return to them later. House of Leaves in particular offers a dense labyrinth of lengthy and/or nested footnotes, such that you are often expected to read them for multiple pages before trying to find your way back to your spot in the main text. (Not unlike an explorer finding their way home via markers they left along their path.)

Some people only ever read the main text, avoiding the footnotes and supplementary materials altogether. Even then their experience is ergodic, simply for how much they end up needing to avoid.

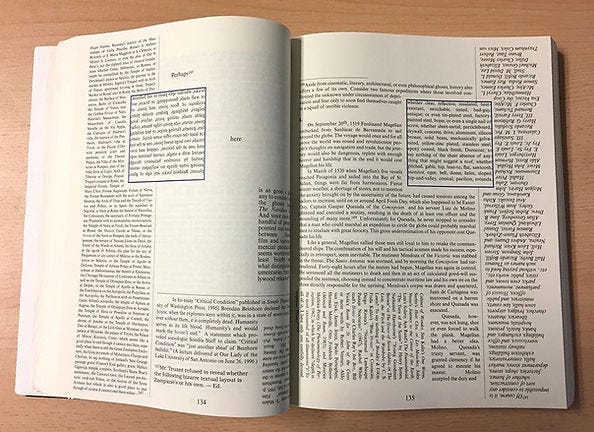

And then there’s chapter IX. (Warning, the image below may disturb you.) Portions of the page become their own tunnels through the text, carrying rambling footnotes listing equipment, architects, films and more. Text is rotated, formatting lines are everywhere. Can you spot the ‘main’ text on pages 134 and 135?

(Ok you got me, there isn’t any on 135.) And to be fair, not all of the ergodic nature of this book is Zampanò’s fault. After all, his manuscript ultimately amounts to a pile of miscellaneous papers stuffed into a trunk. It’s another character, Johnny Truant, who tasks himself with assembling this into House of Leaves, and who is likely responsible for the alien formatting of so much of the text.

You might be sensing a pattern here, as we traverse the narrative layers. Navidson and Zampanò, in whichever order you prefer, both becoming deeply fixated on an unconquerable idea. Will Johnny suffer the same fate?

Yes. 1000%.

—

I’ll try to wrap this up in the next post with Johnny, the Editors and The Whalestoe Letters — but perhaps that will require another split.

Thanks for reading and until next time ❤